The final month in Doug’s archaeology blogging carnival, the final question to answer. Doug asks,

“where are you/we going with blogging or would you it like to go? I leave it up to you to choose between reflecting on you and your blog personally or all of archaeology blogging/bloggers or both. Tells us your goals for blogging. Or if you have none why that is? Tell us the direction that you hope blogging takes in archaeology.”

So this is maybe the last off-topic post that I shall write on this blog. It’s been great fun to be involved and it’s helped me to find new bloggers to follow. At the moment the main audience for my blog is me myself as I work out what blogging is all about; but I am sure that Mike Pitts has it right when he blogged about the need for specialists in general and archaeologists in particular to use vehicles such as blogs to reach out to wider audiences. He writes,

“For the professional archaeologist, a blog or website can be approached in the same spirit as an academic publication – care taken with grammar, style, facts and illustrations will repay itself. The chief difference between a journal article and a blog need be no more than reach, between a readership of a hundred or so and millions.”

That’s where I would like not only mine but also other heritage-focused blogging to be going – to communicate with wide-ranging audiences. Not necessarily each blog, because some will remain specialist and targeted by necessity; but taken together, to be in touch with as many different people as possible.

This conviction led me to take a broad look at the blogs that I am currently following; 21 blogs appearing in my WordPress Reader, one I pick up through RSS and two via e-mail. Why do I follow them and what can I learn from them? Where are they going? Here are a few observations based on the 21 blogs in my Reader.

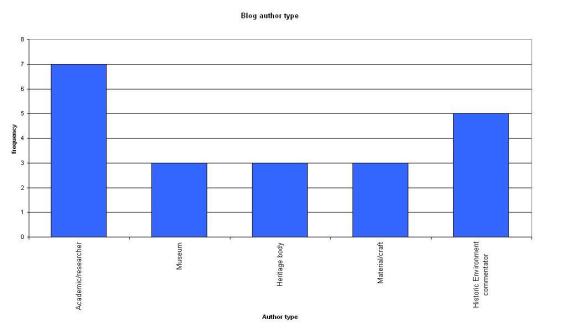

Seven of the blogs are written by researchers at various stages of an academic career – everything from doctoral researcher to professor. Of the three museums, two are regional and one international in scope (some of the other museums that interest me do not blog (yet), but I stay in touch via other social media). “Heritage body” = a team within a national charity, a government agency and a conference whilst “Historic Environment commentator” comprises independent individuals or organisations. “Materials/craft” speaks for itself. In general I follow these blogs to be informed; to be educated; to keep up to date and in touch. I like learning from posts that extended my limited knowledge in various areas of archaeology/history theory and practice that aren’t my specialism; getting news about research progress, exhibitions, field projects, upcoming activities and events; finding out about inter-disciplinary research and interesting collaborative projects; exploring mixed-media posts that illustrate craft and manufacturing skills.

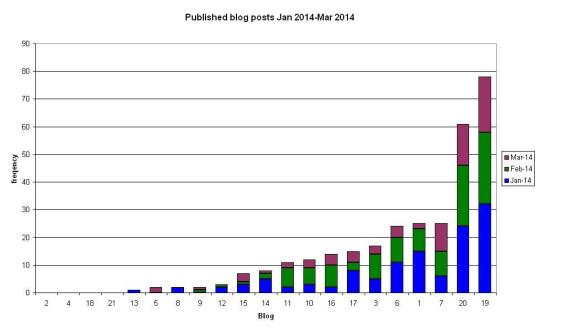

Here’s what I don’t like – distracting moving images on the page, too many exclamation marks, delivery that is just too “matey”, not being able to access all my blogs in one place [maybe I can display them all in the WordPress Reader, but I just don’t know how – any advice?]. Most of all I dislike (a) inaccessibility (my county Historic Environment Record and Archive Centre has a blog on the council website, it has great content but no “follow” or RSS button so the only way to find out what’s new is to remember to visit the website or follow links from the monthly newsletter – hopeless); and (b) infrequency. Whilst I don’t want to use up all my time reading blog posts and not writing my own, it is frustrating to find an interesting blogger and then never hear from them. This chart shows how many posts each of my 21 bloggers has published in the current quarter (we’re not quite at the end of March, because I want to fit this into the blogging carnival, so the figures will have changed slightly by the end of this month):

The frequency of blog posts published by the blogs I follow, for January, February and 1-23 March 2014.

Having counted numbers of posts for this quarter and not a whole year, I can’t tell if my figures represent any seasonality in posting volume. Nevertheless, the two most prolific bloggers, numbers 20 and 19, are both from the “Historic Environment commentator” class. These two blogs’ remit is advocacy for the historic environment, and are run by independent groups who are concerned to raise awareness of threats to archaeology, both in the field and in museum collections around the world, and historic landscapes. No surprise that these are very active blogs.

In contrast, four of the bloggers I follow haven’t posted yet in 2014; yet they have good past content. Blog 8 is the conference; this convenes in early January each year, so naturally it’s not posted in February or March. What’s more surprising is that the museums, blogs 2, 5 and 3, are not more prolific. Number 3 is the British Museum – with so many departments and projects I would have thought blogging might have a higher profile for outreach and communication purposes? Likewise blogs 9 and 11; these belong to national organisations. Are they worried about information-overload for their followers; or do they experience other constraints in their use of social media?

I have chosen to follow these bloggers – and I want their content – so I have to assume that my followers also want my content. Lesson learned – keep posting!

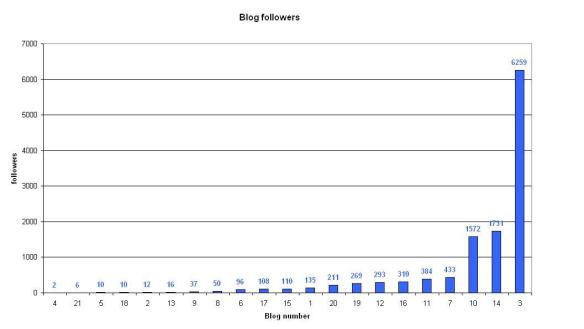

I also looked at the each blog’s number of followers. The figures come from the summary that the WordPress Reader gives when you select one of your followed blogs. These numbers are often different when you look at the counters that bloggers have on their pages, so I guess WordPress is only counting WordPress followers and not all followers using all platforms?

First, we must bear in mind that I have taken no account of how long these blogs have existed. It is reasonable to assume that longer-lived blogs are more likely to have more followers, whilst new bloggers have yet to attract their audience. Secondly, my figures are based on the WordPress count only.

Nevertheless, the run-away winner is the British Museum with more than 6000 followers. The next nearest, yet not that near with under 2000, is a “Historic Environment commentator” – one whose face and name are familiar from the TV, who writes entertainingly about archaeology and other topics with equal fluency, and who is passionate about the subject. Blog 10 is written by an academic, high profile in their own circle, whose cross-disciplinary research must draw in readers from a range of subject areas. Everyone else comes in below 500 followers. Working backwards on the X axis from blog 7 to 17 we have: an academic; a heritage body; four historic environment commentators; three academics.

The point that I am trying to make here is that my blogs with the most followers (blog 3 followed by blog 14) have equally high-profile authors – one of the most famous museums in the world, and (arguably) one of the most famous living archaeologists, at least in Britain. Discounting the conference for the moment because it is a special case, the two other organisations in my “Heritage Body” category – both national, well-established and high profile – should I think expect to have much bigger followings. Their blog content is (mostly) good. Perhaps the online audience demographic differs from their huge offline audience? Or perhaps they suffer from their organisations having multiple blogs, disproportionally promoted? Where do they think they are going with blogging?

If I want to connect with a bigger audience – whether people who already go to pains to pursue their interests, or who are trying to find their way in – I need to think about how they will find me. Lesson learned – get internet-savvy and continue to make connections!

To round off, I want to return to something that Mike Pitts wrote in December 2013 (see the link above to his “Talking Archaeology” blogpost). Mike is an experienced archaeologist, journalist, and editor of popular archaeology magazine British Archaeology. He agrees that there are “undoubtedly important digital opportunities that archaeologists can take greater advantage of”. He comments on the flexibility that blogs offer, how they can be used in different ways for different ends (excavation diary, topic-focused commentary etc). But most of all he stresses that “what matters most is not the medium but the message. In an unpredictable and fast changing media world, one of the few true constants is the value of content.”

Mike’s blog is full of great content, his ongoing coverage of the Richard III story being a case in point. “Heritage bloggers” have great content, and we could and should be the best advocates for the historic environment, for research, for museums, for skills; for all the things that we love and are enthusiastic about.