How do you go about getting stuff? I mean good stuff, not any old stuff. Good oil that won’t ruin your engine. Good netting that won’t rot. Good brushes whose hairs won’t fall out. Good shoelaces that won’t snap. Good valves that won’t leak. Good washers that will hold.

Maybe you rely on brand names, recommendations, or reviews. Or look for kite marks or British Standards. Perhaps you just buy what you always buy. If you have a choice of, say, apples, most likely you use your senses and experience to make a selection. You know what rotten apples look, smell and feel like.

I have been thinking about procurement – getting stuff – because of the problems that I’ve had recently, with wood in particular. How to go about finding good stuff, not just any old stuff. And how archaeologists can think about how people found good stuff in the past, when the landscape, ecology, and natural resources familiar and available in prehistory are so different now. Not only good stuff – what about just making do with what you have got? So I went for a walk, to think about where the Burderop Down sarsen stone came from.

Here’s the archaeological background. During the 1970s Chris Gingell (1980, 1992) carried out fieldwork across parts of the Marlborough Downs. At Burderop Down, the excavations revealed spreads of sarsen stone which were interpreted as working floors; the waste left over from the production of saddle querns in the later Bronze Age. Sarsen boulders cleared from the surrounding fields were gathered together and shaped, by knapping, to make the querns. The querns, “so common on Wessex sites”, were then distributed around the countryside (Gingell 1980, 215).

Now a lot of sarsen was recovered during these excavations. A lot. Last time I added up the Wiltshire Museum catalogue entries I counted nearly 400 bags of sarsen pieces from the Burderop Down dig. The site is located on the north-facing slope of the chalk scarp on the northern edge of the Marlborough Downs, just to the east of Barbury Castle. It is about 6km away from the best known areas of sarsen stone to the south, on Fyield Down for example, but well within the general geological range within which the rocks are found.

What evidence is there now for sarsen stone on Burderop Down? Where did the people making those querns get their rocks from? Good, fine-grained sarsen stone that could be broken in controlled ways to make the characteristic shapes of saddle querns. And other types of stone, like flint, to make pecking stones to prepare the quern surfaces for crushing cereal grains.

Having left the car in the Barbury Castle car-park, the walk starts back down the lane for 200m before turning off to the footpath heading east on the 260m contour line. Almost immediately comes the first sign that there is sarsen in the area:

A standing stone, looking out over the valley towards Ashbury and White Horse Hill there on the horizon. The megalith isn’t prehistoric, though. It’s a memorial stone, commemorating local author Richard Jefferies and poet Alfred Williams. The memorial is a great example of how variable sarsen stone can be. In this one boulder there are areas of fine-grained saccaroid sarsen, rough areas full of fossilized root holes, and a range of colors, because of the variety in the Tertiary deposits that were cemented together to make the sarsen.

Walking along the footpath towards Burderop Down, there’s not much to suggest that there was ever much sarsen stone lying about here. Here’s a piece in the track:

but there isn’t any more to be seen around. And it’s only another 600m before we reach Chris Gingell’s sarsen working site, in the grassy area in the bottom right of the next photo. That round earthwork, with those scrubby trees, is a large disc barrow first excavated by Passmore in the 1920s and again by Gingell in 1979. Behind it is the sarsen quern manufactory.

I love the arguments between visitors, carried out in graffiti on the adjacent sign board, about what the disc barrow earthworks are thought be be:

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Hardly any sign of sarsen at all, until you look closely at the upcast from the molehills that are dotted about:

There are scrappy fragments here and there. Unlike villages south of Broad Hinton on the Winterborne, or Avebury, or the Kennet valley villages for example, there aren’t even any sarsen gateposts to keep up the morale of the dejected sarsen-seeker. It might look beautiful, but it doesn’t look like there’s any sarsen left on Burderop Down.

But just a couple of hundred metres east, and look, what’s that in the hedge line? A sarsen! From here, following the footpath south-east, there are some stones – dragged out of the cultivated areas and left at the field edge.

As well as the occasional sarsen – and I mean very occasional – there is plenty of other agricultural rubbish, broken up chalk hauled up by the plough, and flinty bits. Sure, you get similar rubbish around the farms a few kilometres to the south, but there you also trip up over all the sarsen. Here you have to hunt it out.

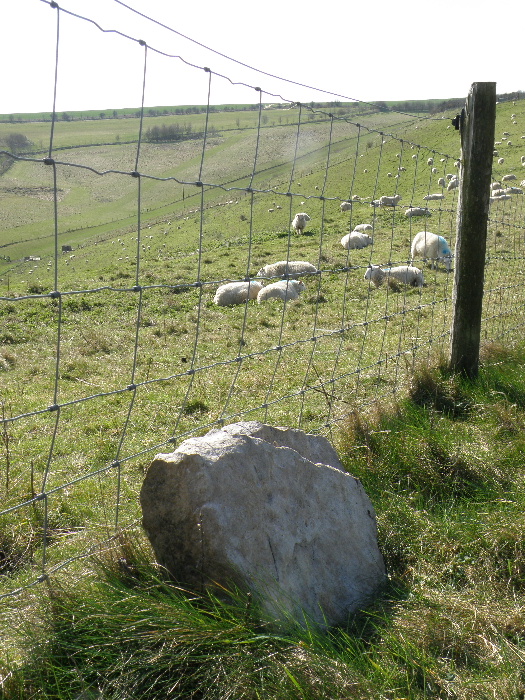

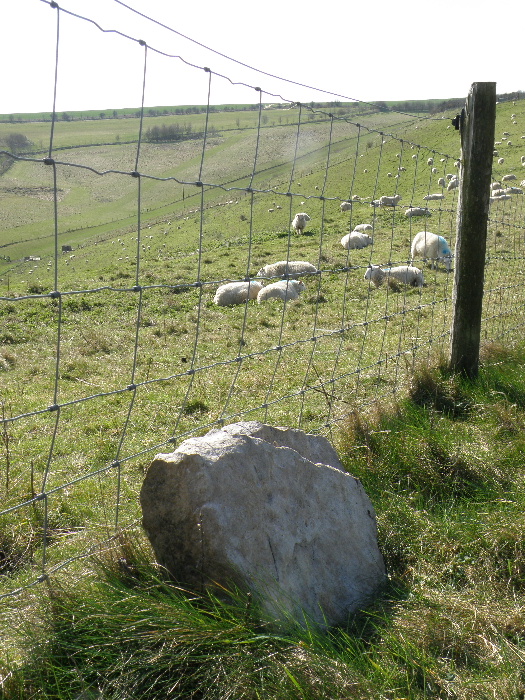

The path continues south-east over the Holywell chalk bedrock where, at a point just west of Ogboune St George, it meets the Smeathe’s Ridge bridleway. Turning north-west, I headed back towards Barbury Castle in the afternoon sun. One sarsen boulder buried in the footpath was the last piece I would see until I found a grey wether impersonating a lamb hunkering against the fence line.

There are still vast quantities of sarsen only a few kilometres to the south, even though people have been taking that stone for 4,500 years. Why isn’t there more lying about here around Burderop too? Where did all the stone for the quern manufactory come from? Has it all been used up, moved, and taken away? And when did that happen? It’s a fascinating topic. Selecting raw materials for certain qualities, using the stone, leaving the remains. Now, the hillsides look so different, cultivation that began in prehistory never stopped.

I failed to find the good stuff on this trip. The experience tells me that different things happened to sarsen on this patch of the Marlborough Downs, only a few kilometres away from sarsen around villages like Fyfield, Lockeridge, Clatford, Manton. It will be fun to tell those different stories.

Gingell, C. (1980) “The Marlborough Downs in the Bronze Age: the first results of current results.” In Barrett, J. and Bradley, R. Settlement and Society in the British Later Bronze Age Oxford: BAR British Series 83 (i).

Gingell, C. (1992) The Marlborough Downs: a later Bronze Age Landscape and its Origins. Devizes: Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society Monograph I.